Anthologies from Hell, Part Two: The House That Dripped Blood

After The Torture Garden, Bloch and Amicus would not make another film together for four years. In that time Bloch continued to write for himself and for television, while Amicus kept trying to outdo and outsell Hammer. During the sixties, Amicus was on the losing side of this inter-England war. That decade resoundingly belonged to Hammer, but the next one would prove more conducive for Amicus’s success. Although the “portmanteau” films had started in the sixties, Amicus really started churning them out in the early seventies. This allowed Amicus to overtake Hammer by 1970. While Amicus was making cinematic versions of the various horror magazines and comics that regularly published Bloch, Hammer was still trying to pump life into tried-and-true characters like Dracula and Dr. Frankenstein, while at the same time upping the sex factor in such titles as The Vampire Lovers and Countess Dracula.

A major part of Hammer’s new, more raunchy direction was the Polish actress Ingrid Pitt. Born in Warsaw as Ingoushka Petrov, Pitt had actually survived the hell of a Nazi concentration camp during the war. After getting married, divorced, and out of California, Pitt found her niche during the height of the sexual revolution. A voluptuous redhead, Pitt made a career out of playing vampire roles which required very little clothing. In both The Vampire Lovers and Countess Dracula, Pitt added lesbianism to her already tawdry repertoire.

Like Cushing and Lee before her, Pitt moved back and forth between Amicus and Hammer, and her first Amicus production saw her working on unquestionably the second most famous film that Bloch ever wrote—1971’s The House That Dripped Blood.

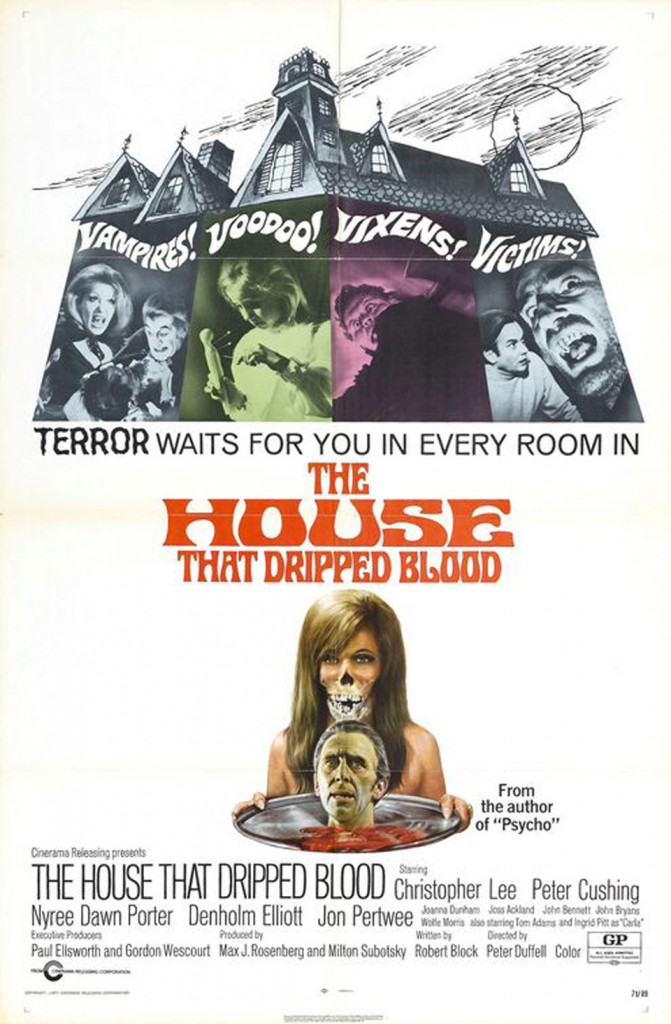

A misleading title since hardly any blood appears in the film at all, The House That Dripped Blood is nonetheless Bloch’s greatest achievement as a pure screenwriter. Like The Torture Garden before it, The House That Dripped Blood is an anthology film composed of four segments and a framing narrative. But unlike Bloch’s earlier attempt, The House That Dripped Blood is an almost flawless pulp composition, with four stories that each work as separate entries. Again based exclusively on Bloch’s own short stories, The House That Dripped Blood has come to be recognized as one of Amicus’s greatest anthology films, if not its absolute best.

Like a lot of horror films, That House That Dripped Blood all starts with a haunted house. The house in question sits in a quiet country lane surrounded by the green English countryside. It’s a red brick affair with large iron gates and plenty of gargoyles. The whole heap belongs to A.J. Stoker (played by John Bryans), a realtor who knows that the place is nothing but evil. He tries to tell as much to the laconic London police officer Detective Inspector Holloway (played by John Bennett). A skeptical hardliner with little patience for the bumbling and bucolic nature of the local sergeant (played by John Malcolm), Holloway has come to the country in order to investigate the disappearance of the famous horror actor Paul Henderson (played by Jon Pertwee, who’s better known as the Third Doctor in the Doctor Who franchise). Sergeant Martin and Stoker tell Holloway that Henderson is just another in a long list of occupants who have experienced strange things, and it is this history which is elaborated on in the film.

In the first episode, which is entitled “Method For Murder,” the horror writer Charles Hillyer (played by Denholm Elliott) and his wife Alice (played by Joanna Dunham) have moved in so that Charles can complete his next book ahead of his publisher’s deadline. Charles sets about his work very quickly, and before long he has a story near completion. It concerns a recently escaped madman named Dominic. Dominic is a strangler. He uses his hands for murder, just like Charles uses his hands for glorifying murder in his books. But as strong of a writer as Charles might be, even he can’t create a murderer out of thin air. And yet that is what happens. Dominic begins showing up out of nowhere and his appearance spells doom for the Hillyer household. First seen outside of his study window, Charles begins to see Dominic (played by Tom Adams) inside of the house. Alice doesn’t believe him nor does she see Dominic, so Charles is sent to see a specialist (played by Robert Lang) who proves to be monumentally unhelpful. As the tension builds, the division between creator and creation blurs right before the story pulls off a difficult double swerve.

After the ingenious payoff of “Method for Murder,” “Waxworks,” the film’s second story, moves in like an old friend. A fairly common horror tale with a plot and a reveal that’s almost elementary, “Waxworks” tells the story of the retired gentleman Philip Grayson (played by Cushing). Grayson is set upon enjoying his new life in the most relaxed manner possible, with hours for reading, gardening, and strolls into the nearby town. Grayson assures Stoker that he “shan’t be bored,” but the quiet reveals that Grayson is suffering from the loss of a dead lover. In an effort to forget about his pain, Grayson visits a local waxworks, where a strange proprietor hosts a murderer’s row that includes a Salome that reminds Grayson of his lost love. The proprietor tells him that he modeled Salome after his own wife, who herself was a murderer.

The night of his visit to the wax museum, Grayson is troubled by a strange dream which plops him right back into the cloying confines of the wax museum. While there, the beautiful face of the wax Salome turns into a deathshead. Grayson and his sanity are only saved by the knocks of his friend Neville Rogers (played by Joss Ackland). The rescue is short-lived however, for Rogers knew Grayson’s lover too, and when he sees the picture of her that Grayson ripped up, he too gets lost in sadness.

The night of his visit to the wax museum, Grayson is troubled by a strange dream which plops him right back into the cloying confines of the wax museum. While there, the beautiful face of the wax Salome turns into a deathshead. Grayson and his sanity are only saved by the knocks of his friend Neville Rogers (played by Joss Ackland). The rescue is short-lived however, for Rogers knew Grayson’s lover too, and when he sees the picture of her that Grayson ripped up, he too gets lost in sadness.

The next morning, Rogers discovers the same waxworks and is immediately captivated by the Salome figure. Indeed, the figure casts a much deeper spell on Rogers, and at one point he lies about a return trip to London just so he can be alone with the figure. Unfortunately, the proprietor proves to be just as possessive of Salome, and the two friends from London end the story as involuntary mannequins in the very same showroom that houses their shared waxen lover.

The film’s third story, “Sweets to the Sweet,” is an adaptation of one of Bloch’s most admired short stories. No less an authority than Stephen King chose “Sweets to the Sweet” as his favorite Bloch short story for the 2000 anthology My Favorite Horror Story. In the screen version, Christopher Lee plays the cold, dictatorial John Reid, the father of a sweet, little blonde girl named Jane (played by Chloe Franks). When a new governess (played by Nyree Dawn Porter) is hired by Reid to look after his daughter, she’s horrified when she learns that Reid does not allow Jane to go outside, associate with peers, or even play with dolls. Reid and Ann Norton, the governess, are bound for conflict, and not long after taking the position, Ann tries to talk Reid into relaxing his strictures.

At first, Ann wins the honor of taking Jane outside, then, after confronting Reid, Ann earns the right to buy Jane toys. Most of Ann’s purchases prove kosher enough, but Reid throws the doll she bought for Jane into the fire under the guise that it’s not “educational.”

It is at this point that the viewer realizes that Reid is deathly afraid of his precocious daughter. On top of that, director Peter Duffell and cinematographer Ray Parslow sprinkle in enough to hint at the fact that Jane isn’t all sweetness and smiles. Specifically, she seems to have not only an odd fascination with the “W” portion of her encyclopedia set, but she also shows an unnatural fondness for playing with wax and collecting hair from her father’s sink. Jane, Reid tells Ann, is a lot like her deceased mother, and that is something to worry about. In fact, Jane’s maternal lineage is deadly, and some don’t escape “Sweets to the Sweet” alive.

In comparison with the other stories, “Sweets to the Sweet” is a slow burn and takes some time to really get going. This touches the back-end, because the final story, “The Cloak,” which details exactly what happened to Paul Henderson before his disappearance, is a noticeably fast number. Despite this, “The Cloak,” which was the Bloch short story that got the attention of Jim Doolittle, the campaign manager for Carl Zeidler, who in turn gave Bloch a job on Zeidler’s ultimately successful mayoral campaign in 1939, is a good, solid horror story that doesn’t deviate from any conventions whatsoever.

The typical overdramatic hack, Henderson is a know-it-all thespian who buys Stoker’s damnable house during the filming of his latest horror film. The film is a cheap-o clunker, and Henderson is not above letting everyone on set know. Along with his buxom co-star Carla Lynde (played by Pitt), Henderson tries to add a little class and star power to his lemon, but everything seems set against him. The sets are flimsy and his wardrobe is a travesty. It is this latter fact, along with a card that is placed on the star’s own dressing room mirror, that drives Henderson to visit a wardrobe and wig shop run by Theo von Hartman (played by Geoffrey Bayldon). Von Hartman proves to be an eerie character with no knowledge of cinema. He does, however, know cloaks, and when Henderson asks for a vampire’s cloak that looks authentic, von Hartman gives him a 13 shillings cloak with alacrity.

Authenticity in this case means that Henderson begins biting his co-stars and growing fangs when the clock strikes midnight. After a coffin is found in the burned-out rubble of von Hartman’s shop, Henderson surmises that his new cloak actually belonged to von Hartman, a vampire himself. When he tells his suspicions Lynde, she replies with the second swerve in the film.

The House That Dripped Blood is a classic 1970s schlockfest, with popcorn butter smeared on the negatives. The only thing that could be said against it is that the Bloch stories that were chosen are some of his earliest efforts. Besides “Sweets to the Sweet,” the other stories used are not regarded as Bloch’s best, and frankly “Waxwords” is downright derivative. Still, The House That Dripped Blood is second only to Psycho in the history of Bloch on film, and unlike the Hitchcock masterpiece, The House That Dripped Blood gave Bloch top billing (although the film’s posters did make it abundantly clear that Bloch was the man who wrote Psycho).

Fin

Bloch only made one more film with Amicus after The House That Dripped Blood. Released in 1972, Asylum once again has Bloch revisiting his older bibliography in order to make an anthology horror film centered on an insane asylum where one of the head doctors recently snapped and started attacking his colleagues. Directed by Hammer veteran and Golden Globe winner Roy Ward Baker, Asylum is a capable thriller that has one or two truly startling visuals.

In “The Weird Tailor,” the suit that Peter Cushing’s character has had specially made for resurrecting his son is placed on the body of an in-store mannequin, which comes alive during a scuffle between the impoverished tailor Bruno (played by Barry Morse) and his wife (played by Ann Firbank). A seventies image to the core, the suit is made of a shiny acrylic material that changes color constantly.

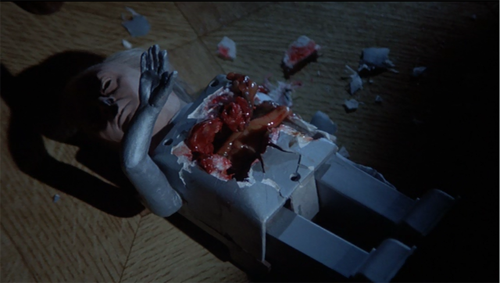

The film’s other noteworthy moment comes at the end when the prospective new hire Dr. Martin (played by Robert Powell) steps on one of the tiny robotic golems created by Herbert Lom’s Dr. Byron. The attack unearths the truth that Dr. Byron’s creations are full of real blood and guts, and it is actually quite stomach churning when the camera focuses in on the red stuff exploding out of the little metal stomach.

After Asylum, which is historically unusual in that its opening and ending credits feature a recognizable classical piece, in this case Modest Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain, Bloch continued to write for films, but mostly he was confined to TV movies. Television work was still there, and for the remainder of his life Bloch continued to write short stories and novels. Bloch’s time with Amicus was, in a larger sense, fairly minor in regards to his entire career. Six pictures out of a sixty-year run isn’t much, but the films that Bloch did manage to make in England are excellent examples of a time when horror films were playing around with the anthology format. No studio did anthologies, or rather the “portmanteau” picture, better than Amicus, and some of Amicus’s best “portmanteau” pictures were written by Bloch. This is only natural, for Bloch was most comfortable with the short story style. And while none of these films can contend with the best of Bloch’s written oeuvre, they do contain those intangibles that make Bloch one of the 20th century’s greatest writers of the fantastique. Lean, outrageous, and fun, the films that Bloch wrote for Amicus are emblematic of one of the great eras in horror filmmaking.