The zombie film, whether you love it or despise it, is an indispensable part of horror’s dark tapestry. Commingling the gothic dark with the gory red, the zombie film helped to transition terror away from the more cerebral towards the more visceral. Some commentators blame this shift on such things as the sexual revolution, which brought a new level of frankness into the popular realm vis-à-vis the bedroom. Other critics point out that the zombie film, which has its roots well planted in the Universal era of the early 1930s, saw its ascension during the turbulent days of the civil rights movement – a time when America (and indeed the rest of the Western world) struggled over questions of institutional racism and economic inequality. In particular, the notion that zombies represent a type of racial “Other” seems clear in such films as White Zombie (1932), which showcases the colonial-like stratification of Haitian society, and George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), which forces a micro society of survivors to rely upon the skills and determination of Ben (played by Duane Jones), the group’s lone African American.

As neat and cozy as this sounds, the zombie film is about much more than just race or sex relations. It is also about the ancient fear of death and the equally ancient distrust of dead bodies. After all, before the wide distribution of antiseptics, dead and rotting bodies were one of the main causes of disease, especially given some of the Old World’s funerary practices. Zombie films are also about violence – senseless, animalistic violence. It should not be surprising then that the truly modern zombie film, which rarely has anything to do with folklore or voodoo, was born in the late ‘60s and coalesced into a recognizable sub-genre in the 1970s. These two decades witnessed a televised war in Southeast Asia, numerous race riots, and a growing upsurge in left-wing and fundamentalist terrorism. In short, the zombie film, like the vampire film, is at its most active during times of unrest and anxiety.

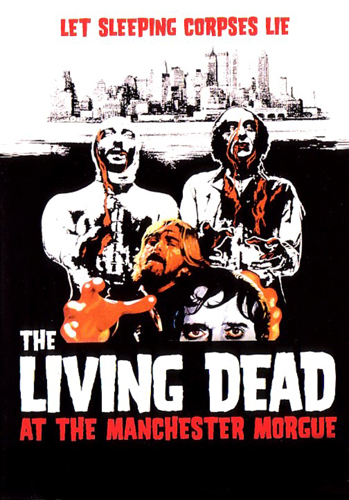

Considering that it was filmed in 1973 and released in 1974 and 1975, The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue (which can also be called a staggering fifteen different names) is a film that deftly captures the zeitgeist of a Europe that was struggling to close the culture gap between the supposedly reactionary old and the increasingly radical young. This Manichean polarity is captured in the film through two characters: the sarcastic “hippy” antiques dealer George (played by Ray Lovelock) and the repressive police sergeant (played by Arthur Kennedy). Added to this battle is the underlying politics of the film’s plot, which involves the resurrection of the recently dead via the use of a new type of agricultural technology that forces pests to attack and kill one another. The fact that this machine, which is owned and operated by the Department of Agriculture, causes the undead to lust after human flesh is a clear commentary on humanity’s ill-advised experiments on the environment.

The film opens with George closing up his antique shop and climbing on his beautiful Norton motorcycle. While he makes his way out of Manchester, the viewer is treated to the sights and sounds of the “Warehouse City.” From the sad-looking people outside of a bus stop to the bizarre woman who runs naked through traffic, Manchester seems like a city that one needs to get away from occasionally. George’s end goal is the Lake District, that tranquil yet sublime piece of English property that inspired the poems of William Wordsworth. Unfortunately for George, instead of spending his time overlooking Tintern Abbey, he is forced to confront the living dead alongside Edna (Cristina Galbó), an easily excited redhead.

After she accidentally backs up into George’s motorcycle with her Mini Cooper, George demands that Edna give him a ride to his destination. After a brief bit of bickering about where they should go first, the two ultimately decide on first stopping off at the residence of Edna’s troubled sister Katie. They invariably hit a dead end (which is set in among some of prettiest country that has ever graced the screen). George leaves to ask for directions and is soon occupied by a new machine that uses ultra-sonic radiation to kill insects. Unbeknownst to anyone at the time, the machine causes corpses to again walk the earth. While George is busy getting directions and scolding the government men who are putting the experimental machine to use, Edna is attacked by a ghoulish man with wheezing breath and outstretched hands. The man, who is wearing wet clothes, chases Edna into the arms of George. As per usual, after listening to Edna’s hysterical ramblings of a male attacker, George can find no evidence of such a person.

From here, the film takes us to the home of Katie (Jeannine Mestre) and her photographer husband Martin (Jóse Lifante). The film makes it clear that these two are not what one would call entirely reputable people, for Katie is addicted to heroin while Martin’s job is to take nude photographs of his strung-out wife. After a fight over Katie’s continued drug use, the same strange man (who is later revealed to be Guthrie, a local vagrant who had recently drowned) attacks the couple, this time making a successful kill. George and Edna arrive only to find a traumatized Katie and a dead Martin.

Despite protests from Edna, George, and Katie, the police, in particular the sergeant in charge of the case, think that Katie is the one responsible. The Sergeant (who remains unnamed throughout the film) points to Katie’s drug addiction as the root cause behind Martin’s death. Not only does this scene point out the motivations of the Sergeant (who is a caricature of the authoritarian, neo-fascist law enforcer), but it also highlights the film’s engagement with topical issues. Director Jorge Grau specifically chooses to not only make drugs and the environment issues in the film, but he also consciously referenced certain true crime events in The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue. Specifically, the attack on Martin and Katie contains all the trappings of the 1969 Manson Family murders (a strange intruder terrorizing a model and her artistic lover), while a later scene brings up the then widely discussed issue of Satanism. After the police respond to a disturbance in the local graveyard involving one of their own (the doomed PC Craig) who had been tasked with tailing George and Edna, investigators suggest that George and Edna might be “devil worshippers” due to desecrated tombs and a broken cross (which the zombies had used as a ram in order to get at the barricaded PC Craig, George, and Edna).

As the film continues, George and Edna try to both convince the police that they are not to blame for the spate of murders in the area and that the government’s new machine is to the reason why the dead aren’t staying still anymore. Like Romero’s earlier film, The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue (which has terribly little to do with Manchester) is set in and around a barren landscape of foreboding nature. Fog is frequent in the film, but more often than naught, the film finds terror into two contradictory landscapes: the sprawling, lonely countryside of northern England and the claustrophobic confines of the village hospital. While Grau’s rural England feels similar to Romero’s rural Pennsylvania, The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue can be argued as a direct influence on Romero, specifically his next installment in his living dead trio – 1978’s Dawn of the Dead. First of all, the zombies in Grau’s film are more man than monster. Not a single zombie in The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue contains an ounce of “too much make-up.” For the most part, Grau’s zombies are wheezing, slow-walking dead men that look the same as they did on the day that they died. In Dawn of the Dead, only a handful of zombies wear more than just the base purple face make-up.

The biggest and most important innovation in The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue is the film’s heightened violence. Taking a page out of Herschell Gordon Lewis’s wet playbook, The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue takes a gleeful delight in showing the gruesome particulars of a zombie feast. In one memorable scene, a small squad of zombies attack and kill a chatty hospital receptionist. After strangling the poor girl, the zombies then target her breasts and stomach, forcibly tearing off bits of skin and muscle and removing whole organs like deranged surgeons. The fact that these zombies (all of whom are male) specifically target these areas will probably ruffle a few female feathers, and it will not in any way help to change the minds of those critics who routinely chastise horror films for their rampant misogyny.

The film ends in a real bloodbath, with zombies, hospital workers, and police falling prey to bullets, teeth, and fire. George and Edna end the film in dire circumstances, with the former being hounded by the police while the latter has to ward off her zombie sister. I won’t tell you who makes it or not, but I can promise you that The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue ends in gory vengeance with a certain party getting their justified comeuppance.

More than just a kitschy bit of ‘70s sleaze, The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue is an important entry in the history of the zombie film. Not only did this Spanish/Italian gorefest escalate the level of violence that is now seen as a requirement in a zombie flick, but its obvious socio-political commentary further developed the sub-genre’s reliance upon real-world fears and anxieties. The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue blazed a low-budget path for all subsequent zombie films, and you would do yourself a favor by spending a midnight watching this forgotten gem.