“Nana, how do you make a deal with the devil?”

It was thirty years ago that one of the most accomplished horror movies was released in Mexico. And you’ve probably never even heard of it. Unlike Japan, Korea, France, Spain, and the U.S., Mexico is not particularly recognized for its horror. Sure, there’s the camp of luchadores fighting supernatural baddies in awful make-up, but a lot of the fare is quite dull. And thirty years ago most Mexican movies sucked.

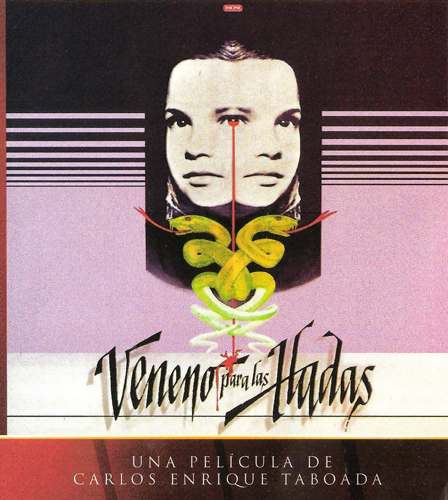

Then there is Carlos Enrique Taboada’s 1984 fright film Veneno Para Las Hadas.

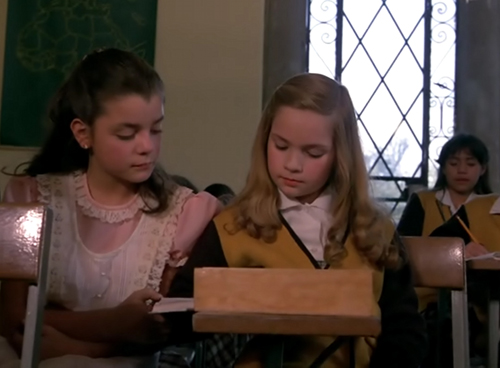

At a time when the principal Mexican cinematic export was the picaresque sexicomedias, this masterpiece thrilled audiences through the creepy presence of young Veronica (Ana Patricia Rojo). Orphaned at a very young age, the angelic little girl was raised by her nanny in a large, old home shared with her invalid grandmother. To distract the precocious child, Nanny tells young Veronica tales of witches and generally unpleasant things. She’s a weird little girl in a strict school; obviously, she has no friends.

New arrival Flavia (Elsa María Gutiérrez) soon becomes Veronica’s slightly unwilling accomplice. They skip school to view the mummies kept in the local museum and to explore the grounds of Veronica’s house. She regales Flavia with exploits of Black Masses and talking stuffed-owls and flying on broomsticks, among other things. A deal with the Devil is soon made, with Veronica affecting such ridiculous seriousness that it’s almost humorously eerie.

When the invocation seems to actually work out—fulfilling what was requested of it by preventing Flavia’s dreaded piano lessons—she becomes scared. In short asides with her parents, however, the coincidental and completely mundane truth about the lessons becomes clear. Unfortunately, no one takes the time to tell this to Flavia. She feels guilty and haunted by her actions.

Veronica uses this guilt to blackmail Flavia into doing her bidding. When Flavia’s family plans a vacation to their ranch outside of the city, Veronica convinces Flavia to take her along. The happy jaunts in the woods and the abandoned church become a quest to make fairy poison, because everyone knows that witches hate fairies and must kill them whenever possible. Veronica, being a witch, must kill the fairies.

When Flavia begins to renege, Veronica uses the aforementioned fairy massacre to extort Flavia into continuing the preparations, even after they are caught and punished by Flavia’s father. Veronica even persuades Flavia into bestowing her with Flavia’s beloved dog Hippy. The sinister child’s delusions grow. At this point, she feels unstoppable and the pressure is suffocating Flavia.

All of this leads to the ultimate, powerful climax as the Witch’s Brew is finally ready to be prepared in the hayloft. In the dark of night, they abscond towards the barn with yappy little Hippy in tow. It is this canine presence that acts as the fulcrum upon which the denouement rests.

This movie relies not so much on visual scares, but rather on atmospheric tension and threats to the innocence of childhood. The faces of adults are shown only twice, with one of these being when the audience sees the face of a corpse. Adult faces are otherwise hidden from sight, only useful for atmospheric effect.

It’s a story of youth—of the world seen through the eyes of children; of adults as knowing entities, elucidated with more understanding about the mechanics of truth and the causes of things that happen.

To kids, so much of the world is unknown. It’s a frightening arena in which the mysteries of adulthood unfold. We are vulnerable to the whims of malevolent beings which will punish us for every misdeed. Monsters lurk in the darkness and in the hearts of strangers. Everything is imbued with the presence of magic. What we lose in adulthood, those things we consider invaluable to our survival, are thrown away as so much dross of folly.

Literature and film are filled with the adventures of children in the world of the unknown, both normal and supernatural. Only they know the truth, while adult logic blinds grownups from seeing the monster that comes out of the basement at night. Or the specter haunting the darkness of the garage. Most of the time it’s a misinterpretation of commonplace events that creates these nefarious realms. Occasionally, maybe children really do see something adults don’t.

The foundation of most childrearing is lies. Santa Claus is real. La Llorona will get you. Go digging around where you ought not, and la mano peluda will get you. Fairy tales are cautionary statements that inculcate social mores and caveats into the impressionable minds of the young. As each layer of untruth falls away, distrust grows. Secrets comprise a huge part of the process of growing up. How much can we trust adults, children ask?

Veronica, in spite of her malevolent activities, is a lonely child at heart. She lacks the oversight and guidance of her parents; it is left up to her loving but immobile grandmother and simple nanny to provide her with her worldview. She is unable to grasp the distinction between reality and fantasy. She alleviates her own powerlessness in an impersonal world through vast imaginings of might. Does this make her evil or simply a child with a childish view taken to an extreme?

When Flavia enters her life, she finds in her a friend and a victim. Flavia is someone with whom she can realize her ambitions. And yet, she feels that her hold slips away quite easily, so she must find ways of keeping her prisoner fettered to her.

One is inclined to think that the villain in the story is Veronica. And why not? She fulfills all of the archetypal qualities inherent to our villains. She’s cruel, ruthless, and wanton. She amuses herself by terrifying others. The human toll of her actions fails to enter into her thoughts. How much of a malefactor can she be, however, when she is unaware of the gravity and enormity of her actions?

With the finale, the viewer is left wondering who might be the actual villain. This is a film that must be watched all the way to the end. Screams of “Flavia!” repeated over and over again will haunt you. You will never look at children the same way.