When something bad happens, and when the perpetrator or perpetrators show the obvious signs of influence from popular culture, the question usually comes up. In this case, it’s always THE QUESTION: does art imitate life, or does life imitate art? It’s rhetorical, of course. The relationship between art and life is akin to the bond between the chicken and the egg. Still, knowing that we know so little never stops people from pinning the blame on those things that entertain us. In 1999, Marilyn Manson, a shock rocker who wanted popular loathing as much as a high rate of ticket sales, was reviled in the press for supposedly being the Svengali behind Columbine. More recently, tragedies such as Newtown and Aurora have been blamed on video games and the bloody shoot ‘em up festivals coming out of Hollywood. Even my grandfather, a normally rational man, once turned to be during a dull wedding reception in order to ask: “Do you think that’s why kids shoot up high schools?” After following his finger, I realized he was talking about a preteen across the room who sported the oh-so familial slouch of someone too engrossed in their own cell phone.

Despite the fact that study after study have found no links between long-term violence and video games, too many people seem too willing to lay the blame of modern violence on modern, exclusively digital entertainment.

Because they’re the opposite of apps and other easily-consumed forms of blue-filtered data, books are rarely held up for scorn or are blamed for fueling the rage of malcontents. The worst you’ll hear anymore is about such-and-such school board’s attempt to ban a book from the curriculum, and even then the do-gooder forces of the “I Love Banned Books” crowd usually win in the end. No, reading novels or short stories is not going to get one pegged as a potential mass murderer anytime soon.

One particular short story though does have a rather interesting track record. Originally published in the January 19, 1924 edition of Collier’s, the aptly entitled “The Most Dangerous Game” (which has also been published under the title “The Hounds of Zaroff”) has left a lasting influence not only on the world of literature and film, but also on more than one serial killer. “The Most Dangerous Game” is and will always remain the best known story ever written by Richard Connell, a newspaperman from Poughkeepsie who came back from the fields of France in 1919 and decided to give freelance writing a go. Although Connell remains one of the few men to ever receive a prestigious O. Henry Award twice (his short story “A Friend of Napoleon” won the second prize in 1923), and after 1937 embarked on a successful career as a screenwriter (Connell’s script for 1941’s Meet John Doe, which he co-wrote with Robert Presnell, Sr., was nominated for an Academy Award), his name is synonymous with the ghoulish tale of the former White Russian nobleman General Zaroff and his drastic attempts to alleviate his boredom.

In brief, “The Most Dangerous Game” concerns a famous big game hunter from New York City named Sanger Rainsford whose ship crashes en route to Rio de Janeiro. After swimming to safety, Rainsford ends up on General Zaroff’s doorstep as an unwitting animal in the middle of Zaroff’s private island. After admitting to Rainsford that he is an avid reader of his books, and after reliving his own battles with both the wild game of the world and the Bolsheviks of his native land, General Zaroff confesses that hunting, even the hunting of tigers, no longer holds a thrill for him. But, luckily for the rick sicko, he’s found a new pastime:

“I’ve always thought,” said Rainsford, “that the Cape buffalo is the most dangerous of all big game.”

For a moment the general did not reply; he was smiling his curious red-lipped smile. Then he said slowly, “No. You are wrong, sir. The Cape buffalo is not the most dangerous big game.” He sipped his wine. “Here in my preserve on this island,” he said in the same slow tone, “I hunt more dangerous game.”

The most dangerous game is man, and in “The Most Dangerous Game,” Rainsford and General Zaroff engage in a vicious game of cat and mouse that ultimately ends in one man’s death, while the victor earns the right to sleep in a warm bed.

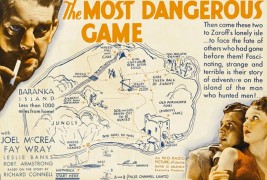

Since first seeing publication, “The Most Dangerous Game” has become one of the most anthologized short stories in the English language, plus it has served as the basis for at least 8 film adaptations. The first, 1932’s The Most Dangerous Game, remains the best of the bunch. Directed by Irving Pichel and Ernest B. Schoedsack and produced by the same men responsible for King Kong (The Most Dangerous Game was filmed at night on the same jungle sets as King Kong during the time when the later monster movie was finishing up its groundbreaking special effects), The Most Dangerous Game stars Joel McCrea as Rainsford, Fay Wray as Eve Trowbridge, Rainsford’s love interest and a fellow shipwrecked survivor, and Leslie Banks as the suavely vile Zaroff (who is demoted to a Count in the film, probably in the hopes of somehow linking him to Count Dracula, cinema’s bestselling monster from the year before). Banks in particular shines in this classic pre-Code thriller, and his brilliant use of his own deformity (Banks was wounded while fighting in World War I, and as a result one half of his face was paralyzed) heightens the inner depravity of Zaroff.

In 1999, the Criterion Collection gave The Most Dangerous Game a lovely repackaging and restoration, calling it “One of the best and most literate movies from the great days of horror.” Now widely regarded as a classic, The Most Dangerous Game spent years as a cult film appreciated by those lucky few who knew where the nearest independent theatre specializing in silent and early sound films was located. One of these initiates saw the film in Riverside, California sometime around May 1969.

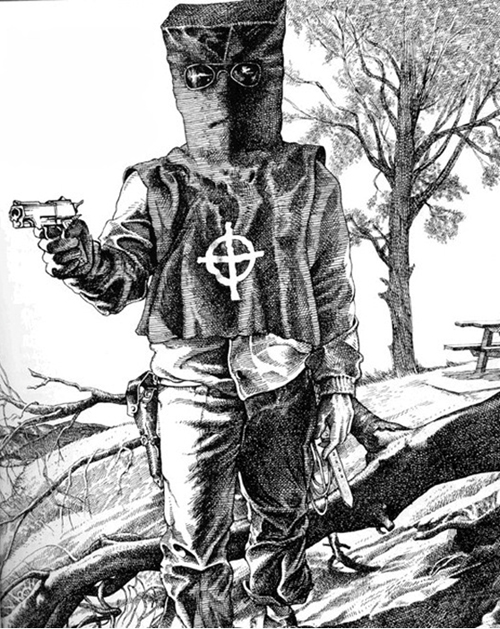

This moviegoer’s name remains unknown, despite decades of public and private sleuths trying to discern it by any means necessary. For us, the most infamous fan of Connell’s story and Schoedsack’s film is simply known as Zodiac. Between December 1968 and October 1969, a series of crimes held San Francisco and the Bay Area in the icy grip of terror. Initially seven victims in total (David Arthur Faraday, 17, Betty Lou Jensen, 16, Michael Renault Mageau, 19, Darlene Elizabeth Ferrin, 22, Bryan Calvin Hartnell, 20, Cecilia Ann Shepard, 22, and Paul Lee Stine, 29), the reign of the Zodiac killer grew in proportion to his own ego. Soon all the unsolved murders in California became the suspected handiwork of the Zodiac, with the most convincing, but still unconfirmed case being the 1966 murder of Cheri Jo Bates in Riverside.

Making everything worse for the already uneasy residents of San Francisco were the derisive letters that the killer sent to the public, especially the newspapers. On Friday, August 1, 1969, the San Francisco Chronicle received one such letter from the Zodiac, who proceeded to provide insider-only details about the double murder of Faraday and Jensen at Lake Herman in 1968 and the attempted double homicide of Mageau and Ferrin on July 4, 1969. Attached with the missive was an elaborate cipher that the killer claimed housed the key to his identity. When it was cracked by a forty-one-year-old history and economics teacher at North Salinas High School and his wife, no name was given, but a clue was indeed provided:

I Like Killing People Because It Is So Much Fun It Is More Fun Than Killing Wild Game In The Forrest Because Man Is The Most Dangeroue [sic] Anamal [sic] Of All To Kill Something Gives Me The Most Thrilling Experence [sic] It Is Even Better Than Getting Your Rocks Off With A Girl The Best Part Of It Is Thae [sic] When I Die I Will Be Reborn In Paradice [sic] And Thei [sic] Have Killed Will Become My Slaves I Will Not Give You My Name Because You Will Try To Sloi [sic] Down Or Atop [sic] My Collectiog [sic] Of Slaves For Afterlife…(emphasis mine)

According to Robert Graysmith, an editorial cartoonist at the Chronicle during the late ‘60s and 1970s who eventually came to write what is considered the seminal account of the Zodiac murders, the Zodiac may very well have taken inspiration from the spirit of Connell’s short story and the stark images of the film. In particular, the Zodiac’s daylight attack at Lake Berryessa in Napa County, which resulted in one death and one serious injury, points towards the Zodiac killer being an obsessive fan of sorts with a deep desire to become Banks’s Zaroff, complete with black clothing and a hunting knife similar to the one that Count Zaroff sports in the film.

Ultimately, the murder of cab driver Paul Stine ended the official body count of Zodiac, but his legend and his legendary threats to the police, plus Scorpio, his stand-in used in the 1971 classic Dirty Harry, continue on with the rest of history’s uncaught serial killers. To this day his supposed reveal remains the stuff of best seller lists. Even in 2014 his true identity was the subject of a book – The Most Dangerous Animal of All – which posits that the writer’s own father was in fact the Zodiac.

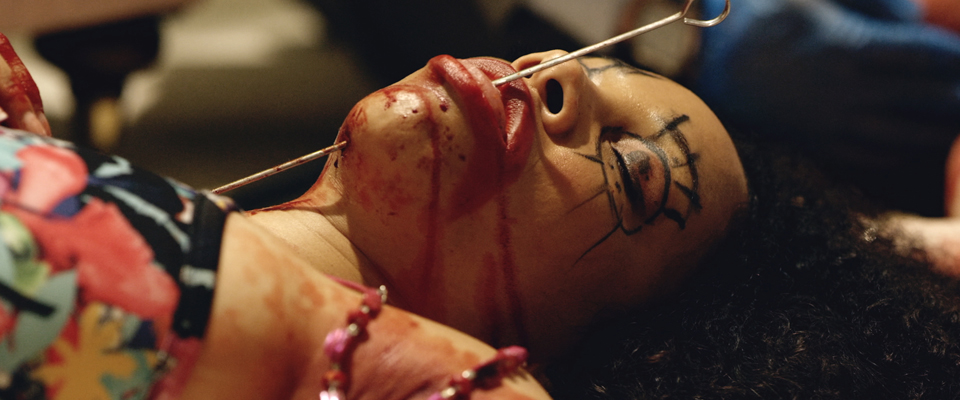

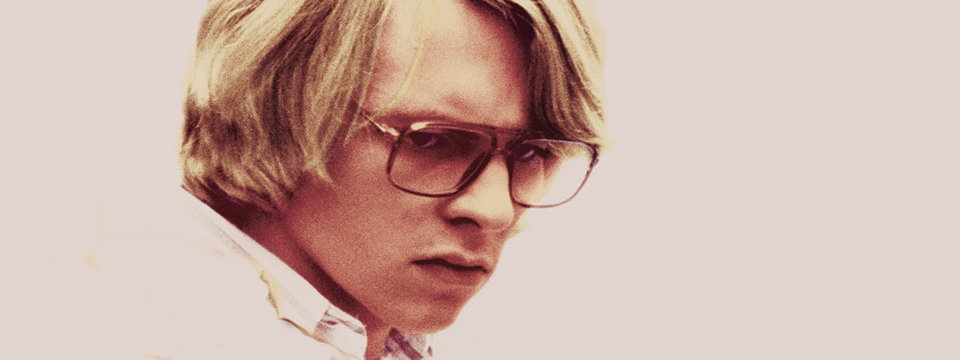

During the height of the Zodiac’s infamy, another killer was busy fulfilling his own Zaroff fantasy. This killer, Robert Hansen, did more than just play dress-up; between 1971 and 1983, Hansen, a bespectacled and bipolar baker based in Anchorage, Alaska, abducted, tortured, and then gunned down several young women, many of whom were prostitutes, in some of the most remote parts of America’s last great wilderness. Hansen’s methods were not revealed until 1983, when the 17-year-old Cindy Paulson managed to escape from the mild-looking and middle-aged Hansen. After first enticing Paulson with an offer of $200 for a single sex act, Hansen grabbed her at gunpoint before taking her captive. While imprisoned in Hanson’s home in Muldoon, Paulson was subjected to torture, rape, and numerous incidents of sexual assault.

The next morning, Hansen drove Paulson out to the Merrill Field Airport in Anchorage with the intention of taking her to his “cabin” (a shack located in the remote Matanuska-Sustina Valley), but Paulson managed to break free of Hansen’s handcuffs while he had his back turned to her. After leading the police to her assailant, investigators began to look into the other allegations against Hansen, and, after searching Hansen’s home and finding not only items belonging to missing women, but also a map marked with approximately 20 gravesites, Hansen eventually confessed to multiple homicides.

Hansen’s method of killing was lifted straight from Connell’s story: after prolonged sessions of sexual torture, Hansen, a licensed pilot, would first fly, then drop his victims off in the harsh no man’s land of rural Alaska. From there, Hansen, an accomplished hunter who decorated his home with his stuffed conquests, would stalk and hunt the women like valued game. In 1984, Hansen pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 461 years in prison. He died in August 2014, a little over a year after the release of The Frozen Ground, a full-length film about Hansen’s crimes starring Nicholas cage and John Cusack as Hansen.

While the Zodiac Killer and Robert Hansen might be the most easily identifiable spawn of the fictional Zaroff, numerous others have taken either direct inspiration or suggestion from Connell’s very savage story. In all its forms, “The Most Dangerous Game” is at its heart a story about humanity’s deep-seated viciousness – our lurking, sometimes dormant, sometimes awake inner beast. Although inspired by the then fashionable pastime of big game hunting among well-to-do Americans, “The Most Dangerous Game” is as notable today as it ever was. Evil and the urge to kill will never go away, and as such “The Most Dangerous Game” can lay claim to being one of horror fiction’s most primal narratives. No wonder then that the most primitive animals among us find it so compelling.