[I received this writing inside of a sealed envelope smeared with what can only be described as a mix of gelatinous ichor, black tea, and delicious homemade tomatillo salsa by way of a mysterious cloaked invalid on prosthetic legs of what appeared to be silver. Along with it came a hand-scrawled scrap of paper with the following writ upon it in the vaguely familiar hand of my good friend and adventurer, the eminent author Anibal Casco: “This is the only copy of the damned work that has driven me to realms unknown to sane men. My research has gotten me closer to things you’d never imagine. Do with it as you see fit, Avila, but by Gods, do not let another pair of human eyes ever glance at it!” Although the scholarly Mr. Casco implored me to destroy it, my metaphysical inclinations persuaded me to publish it to avoid denying the world his genius. The author has not been heard from since, disappearing while perambulating along the banks of a well-known river. I may regret this, for already the angles of this study seem to bend and quiver into non-Euclidian angles unfeasible in our own dimensional regions.

-Int. Arturo Avila]

Tuesday, March 15th marked seventy-four years since the death of that eldritch, unequalable master of the horror genre who gave the world a taste of true cosmic horror. Intestinal cancer, Bright’s disease, and general chronic malnutrition stole the good Howard Phillips Lovecraft on March 15, 1937 at the age of 46 after enduring several months of unspeakable and horrifying pain that drove him to utter madness. Well, perhaps not so much unspeakable and horrifyingly maddening, but the turn of phrase certainly suits the uniquely wordy diction of Mr. Lovecraft.

With the loss of H.P. Lovecraft, the world of words lost more than just the connection to a style of writing deeply influenced by Lord Dunsany, Poe, and a myriad of other wordy auteurs, but also to a fertile imagination more in line with Nietzschean super morality than with the mainstream mentality of Good versus Evil. In effect, Lovecraft wrote of The Colour Out Beyond Good and Evil. In writing his pantheon of creatures, deities, and alternate dimensions he created an entirely new mythos, one where humans are little more than insects in the path of somnolent and ambitious creatures. There was no real good versus evil in the Lovecraftian sagas; we are merely there by coincidence.

In spite of never having traveled further than New York City from his native Rhode Island, Mr. Lovecraft traversed a vast creation with the aid of his pen. From the stifling deserts where lost cities hide under the drifting sands to chthonic realms inhabited by ghouls; whether his characters made their voyages on car, ship, walked ancient streets, or even projected their minds across space and time into distant worlds, there was no dearth of adventure for the reclusive and strange man. He also experienced the world through his voluminous correspondence with people from all over, especially fellow authors. Many of these letters have subsequently been published in collections where his wit, opinions, and occasionally even artwork can be appreciated. Although never able to continue studies in astronomy due to his inability with higher mathematics, he maintained a life-long interest in this field as well as biology.

Born on August 20th of 1890 in Providence, Rhode Island, Howard Philips Lovecraft was born to Winfield Scott Lovecraft and Sarah Susan Phillips Lovecraft. The elder Mr. Lovecraft was a traveling businessman who dealt in precious metals and jewelry. He went on to suffer a sudden psychotic episode in a Chicago hotel room, experiencing episodes of madness until his death. These were probably syphilitic in nature. After his father’s death, the young Howard was raised by his mother, two maternal aunts, and his grandfather in their stuffy old mansion.

After the de rigueur, troubled and isolated childhood in which frequent illness kept him from school and where his grandfather inspired a love of the literary and the strange, the prodigy that would become H.P. Lovecraft made his inauspicious beginning by writing mainly poetry during his teenage years until a lively debate apropos the insipid nature of the stories in a pulp magazine inspired him to write his own fiction. When he first began to write, his fiction was a weak imitation of the authors that had influenced his fertile imagination. In reading his early works, one finds that they read like the stumbling first steps towards a definite end goal, however distant and hazy it may appear. As time progressed, however, the stories that could have passed for a badly done copy-and-paste job of random Poe, Dunsany, Hawthorne, and Machen paragraphs began to evolve into the desiccated, yet not wholly flavorless, style of what would become known as Lovecraft’s Cosmicism.

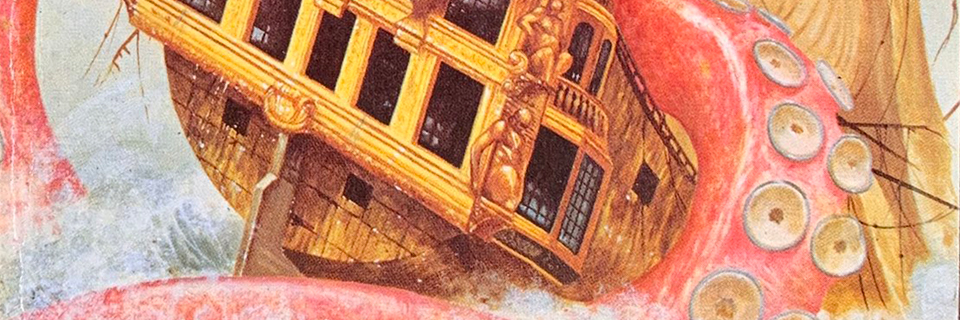

Among the things Mr. Lovecraft left to this world, the most well-known is Cthulhu and his associated cult. This massive cephalopodan deity slumbers in the city of R’Lyeh, a huge sunken metropolis somewhere near Antarctica in the desolate South Pacific, until it is time to awaken to serve its masters, the Great Old Ones. Though little is made specifically clear about any of the creatures in Lovecraft’s stories, the reader becomes aware that these Great Old Ones are ancient, gargantuan extraterrestrial deities with varying degrees of contempt for humanity and who co-exist with the other pantheons like the Outer Gods and the Elder Gods. The fictional cities of Arkham, Dunwich, and Innsmouth and Miskatonic University are other major contributions from Lovecraft.

Today, his influence has spread into almost every facet of art across vast yawning gulphs of time and is seen easily nigh on anywhere, with the horror and science fiction genres especially showing this. Even during his lifetime, noted authors such as Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, and Robert Bloch contributed in building what would later become known as the Cthulhu Mythos, borrowing locations, characters, and creatures from his stories in a mutual exchange of lore to build the strange universe of pulp horror. Even decades after his death, the Cthulhu Mythos has steadily grown like a pandemic long after Patient Zero is dead.

Authors have continued to contribute to the Cthulhu Mythos while Innsmouth, Arkham, and Miskatonic are frequently mentioned long after his death. His characters have appeared directly or indirectly in the works luminaries like Neil Gaiman, Stephen King, Alan Moore, Clive Barker, and Jorge Luis Borges, all of whom cite him as a major influence. The many subtle tendrils of Mr. Lovecraft’s work weave into every facet of art, even those that aren’t necessarily logo centric. In the Batmaniverse, villains are sent to Arkham Asylum and many of H.R. Giger’s paintings have obvious references to Lovecraft. Many movies have been made that use the varied progenies of his genius as plot points. The most famous posthumous publisher of Lovecraft’s collected works, as well as those of other weird fiction authors, has been Wisconsin’s Arkham House publishing. This publishing house was founded by two of Lovecraft’s friends and contemporaries, authors August Derleth and Donald Wandrei. A brief search on the internet can bring up many items bearing the logo of Miskatonic University or the cities of Arkham or Dunwich.

I first became acquainted with Lovecraft as a child in those strange aeons around fourth grade. By then, I was the weird, creepy child haunting the recesses of the library where the books on less popular subjects were confined. My obsessions were manifold, from cartoons to mythologies, aliens to cryptozoology; there was never anything too out-there for me. Thus, through my pillaging of this small and somewhat lacking collection of books about aliens, ghosts, vampires, time travel, and the classics of Isaac Asimov, et al., I would come across references to myriad Lovecraftian things alluded to like a distant Oriental legend and held only by a gossamer strand to anything more accessible than the fabled Necronomicon of the Mad Arab Abdul Alhazred.

The first definite encounter I had with Mr. Lovecraft was when I read “At The Mountains of Madness” at the Beloit Public Library when I was in fifth grade. Or rather, I should say I attempted to read it. Try though I might, the inferior intellect residing in my brain had not yet developed enough to plod through the tangle of words that is Lovecraftian fiction. Undeterred, I continued to explore the manifold weirdness in the world and his writings until I could finally get through Mr. Lovecraft’s works.

Today, with the recent anniversary of his death as a stark reminder of the passing of a cyclopean figure, my own thoughts turn to the influence he has played not only on my style but on the style of many of those that have in their turns influenced me. The unique mind of a unique man has passed from the shadows of the dreary pulp magazines to the book cases of people I consider my heroes. Lovecraft fhtagn.