Greetings, fear fiends! It is certainly true to say that we lovers of the macabre and the morbid are not satisfied with just one scary story…we like them to come in bunches! Hence, the great popularity of horror anthologies, in both printed and film form. As a young medical deviant, most of my exposure to horror came from numerous books collecting time-honored classics by authors like Poe, Lovecraft, Matheson, Bloch, etc. And then of course there were those gnarly and depraved horror comics like DC’s House of Mystery, Marvel’s Where Monsters Dwell, the more adult Eerie and Creepy and finally the truly disgusting filth like Tales From the Tomb and Weird Tales, bursting with flesh-eating zombies and mutilated corpses. From such twisted tales was Dr. Mality created.

Many of those comics, especially those from notorious EC Comics, served as inspiration for movies that combined several horror tales into one package. These anthology movies have provided some of the biggest chills in cinema history, with many coming during the glory days of the late 60’s/early 70’s. British studio Amicus was the master of the form, producing classics like Tales From the Crypt, The Vault of Horror and Asylum. There have been peaks and valleys in the history of horror anthologies but the art form has never been totally absent. Creepshow ignited another flurry in the 80’s, leading to a slew of “made for video” collections.

To cover all the various horror anthologies released through the years would beyond the scope of this article. I will therefore train my microscope on four wildly different variations of the theme, each from a different decade and reflecting a different horror focus. Here are the movies I’ll be looking at:

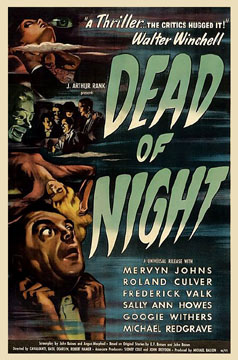

Dead Of Night (1945): This British film was the first true horror anthology film and influenced all that followed it.

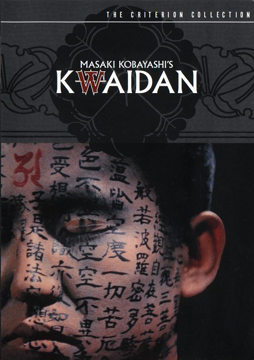

Kwaidan (1964): An unusual and beautifully directed Japanese anthology film based on samurai era ghost stories.

Tales From The Crypt (1972): Perhaps the archetypal horror anthology, adapted from EC Comics.

Tales From The Hood (1995): This movie adapts the classic horror anthology format to a gritty African-American environment.

And now, as the Crypt-Keeper might say, let’s lace up our booties and take the graveyard path…

DEAD OF NIGHT

This is the grand-daddy of them all; the template for all that came after and in the opinion of many, still the best. Not only was it the first horror film to feature multiple stories, it also introduced the important concept of the “framing sequence” — a story outside the others that links them all together. Dead Of Night’s framing sequence is still the most chilling and brilliantly executed of them all.

The movie came out in 1945, a year during which horror films of any kind were scarce. The smoke from World War II had barely cleared and many Europeans were hardly in the mood for downbeat or scary entertainment. Nevertheless, Dead of Night was a product of the highly regarded Ealing Studios and by sheer force of its quality managed to succeed. It was certainly a much more sophisticated kind of horror than what was coming out in the States in the same period — the tail end of Universal’s “Mummy” cycle and poverty row horrors from Monogram and PRC.

Several directors worked on the project. This resulted in the film having a look that was unique and yet cohesive. Of all the stories, the “Ventriloquist Dummy” segment is by far the most famous and inspired many later films and stories such as the 1978 Anthony Hopkins classic Magic. That story is supremely creepy and incredibly well acted by Michael Redgrave in the lead role, yet my actual favorite is the Dead Of Night framing sequence itself, a masterpiece of subtlety.

The film opens as the car of architect Walter Craig pulls up at a beautiful country mansion. A confused Craig enters the house, where guests have gathered for a party, and tells them they all look familiar although he has never seen any of them before. He also seems able to predict events that are going to occur. The skeptical psychiatrist Dr. Van Straaten is fascinated by Craig’s behavior and a discussion about the supernatural begins. Each of the guests winds up telling their own tale of the weird and so we have our film.

The first story is the “Christmas Party” sequence (cut from the original American release and later re-added), told by character Sally O’hara and directed by Alberto Cavalcanti. It tells of Sally’s visit to a stately manor for a Christmas party where many of the party-goers are dressed in period costume. During a game of hide-and-seek, Sally finds what seems to be a hidden staircase, which leads to a bedroom where a small boy is crying. When Sally tries to find out what’s wrong, the boy tells her “She hates me…she’d like to kill me!” Sally quiets the strange young child and puts him to bed. Returning to the party, she tells of the experience and learns that she has just seen the ghost of a boy murdered long ago.

This is an old fashioned ghost story given a lot of extra oomph by how seriously it’s told. Because Sally reacts so strongly to the experience, so do we and we feel a melancholy kind of chill realizing the poor boy was murdered and will haunt his hidden room forever more. Not a story with a jolting shock of terror but an agreeably creepy feeling.

Second story is “The Hearse Driver” and it’s one of the oldest ghost/premonition stories in the book, later remade as a modern Twilight Zone episode Twenty-two. In our time, the story has become predictable and clichéd, which hurts its horror value, but in 1945, its impact had to be very strong.

A race car driver recovering from a serious crash is restlessly staying at a hospital and finding it impossible to sleep when he notices it is suddenly broad daylight outside when it should be night. He goes to the mirror and is shocked to see a hearse parked outside. The queer looking driver smiles at him and says “Room for one more, sir!” The driver wakes up from what he thinks is a nightmare and finds it’s still night out. The next day, he’s released from the hospital but as he gets on the bus, he recognizes the driver as the man from his dream. “Room for one more, sir!” the man cheerily tells him. Experienced horror fans can guess the rest. It’s a morbid little sequence, but undoubtedly much more effective in 1945 than 2012.

Segment 3 tells the story of “The Haunted Mirror” and it’s the most chilling so far. Tales of cursed mirrors have been done elsewhere in horror history but never in such direct and compact fashion as this. It’s the tale of Peter Cortland, whose wife buys him a peculiar antique mirror in one of those quaint curio shops so common in horror anthologies. Peter looks into the mirror and believes he sees a much different room than the one he’s actually in – a room from another time. And the more he looks at it, the more he feels himself being called into that other room…by the people who are living there.

This is another great morbid ghost story with a powerful and scary climax. Along with “The Ventriloquist” story and the framing sequence, it’s where the real horror in “Dead Of Night” comes from. The idea of the dead past reaching into and claiming the living is an especially eerie one and considering the brief amount of time the story is given, it works very well here.

Most anthologies will include a more light-hearted tale to lighten the tension usually before the final and often scariest story starts. In the case of “Dead of Night”, it’s “The Golfers” segment that does the trick. Some feel this tale really doesn’t fit in the anthology while others say it just shows the range of storytelling.

Mr. Potter and Mr. Parratt are two incredibly British chaps who are the best of friends and the worst of rivals, especially on the golf course. Now they are each fighting for the love of the same woman and they decide to solve the matter by having the ultimate high stakes golf match. Parratt does a little bit of cheating and Potter loses the match and the woman which causes him to promptly drown himself in a pond. But death is not the end for Mr. Potter. He returns as a ghost to haunt his golfing partner. The final scene here shows that some people deserve each other…even after death.

It is true that the “Golfers” segment is as tweedy and stiff-upper-lip British as you can get, which probably works against it outside of Old Blighty. There are some dry chuckles here but not much in the way of fright. Still, I think it’s a very important part of Dead Of Night as a whole and what’s more, it’s based on a short story by none other than H.G. Wells!

“The Golfers” sets the table for the final story, “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy”. Simply put, this is one of the most unforgettable horror tales of the Golden Age and anybody who’s creeped out by ventriloquist dummies or dolls had best avoid it altogether. Where “The Golfers” is a comedic tale and the other stories, even “The Haunted Mirror”, feature endings that come as a relief, this one is unrelentingly grim and tense, with an ending that still packs a punch today and must have been shocking in 1945. It features an Oscar-caliber performance from Michael Redgrave (father of Lynn and Vanessa) as the tormented ventriloquist who seems to be fighting a losing war against his own dummy.

Redgrave plays Maxwell Frere, a successful ventriloquist who is in jail for attempted murder. When questioned by the police, Frere tells them “Hugo is more to blame for this than I am.” Hugo is Frere’s rather repulsive looking dummy, his constant partner.

During a flashback, we discover that Hugo seems to have a mind of his own and is interested in dumping Frere to join the successful American ventriloquist, Sylvester. Sylvester, meanwhile, is trying to learn just what makes Hugo so life-like. A bizarre psychological tug-of-war seems to be going on between Maxwell, Hugo and Sylvester, a war that Frere is definitely losing.

Is Hugo really alive or has Frere’s mind gone so far around the bend that he imagines himself to be Hugo? That’s the question that lingers and the final scene of this segment is one that will make the hair on the back of your neck stand up.

“The Ventriloquist” is the last story to be told to our friend Mr. Craig. And it seems to have triggered something awful in him. He now remembers why he’s in the mansion. He also notices the large mirror on the wall, the strange little boy sitting in the corner and finally, the horrific ventriloquist dummy walking under on its own power towards him…it’s a nightmare! Or…is it?

The whole horror anthology concept got off to the biggest bang possible with Dead of Night. Almost 70 years after its release, many hold it to be the best example of the format. I’m not sure if I completely agree, but it is very good and holds up quite well. It also succeeds by virtue of being different. It doesn’t resemble anything else from its time, although it is close to the Val Lewton School of intelligent horror.

KWAIDAN

1964 brought one of the most unusual and beautiful examples of the horror anthology to life, the Japanese film Kwaidan. This film has such a different look and feel to it; it stands virtually apart from all other examples of the anthology form. It’s a very strong tribute to how the multi-story format can adapt to different cultures.

Directed by Masaki Kobayashi, the title translates simply to “ghost story” and is adapted from a book by a remarkable man named Lafcadio Hearn. Hearn’s own story is so fascinating that it’s worth a digression to examine. Patrick Lafcadio Hearn was born in 1850 on the Greek island of Lefkadia (hence his name) from a mixed English-Greek marriage. He spent most of his childhood in Dublin, Ireland before emigrating to the U.S. as a student. There he became known as an eccentric firebrand who was always on the warpath against corruption and ignorance. He was briefly married to a black woman, an ex–slave, which was considered a major scandal at the time. He was forced to divorce his wife and leave town for New Orleans.

Hearn became fascinated with the lurid culture of New Orleans and wrote often about voodoo rituals, sensational murders and the city’s cuisine. From there, he journeyed to the Caribbean, but at last ended up in Japan in 1890. Hearn became completely immersed in the language, culture and folklore of Japan. He became one of the very few “gaijin” (foreigners) accepted into the inner circle of Japanese storytellers. This was the period when he wrote the book Kwaidan, a collection of chilling ghost stories from Japan’s feudal past. It remains by far his best known work, even though he was a prolific writer. Hearn married a native noblewoman and even changed his name to Koizumi Yakumo. He died at the young age of 54 in 1904. To this day, no westerner has penetrated the depths of Japanese culture as much as Lafcadio Hearn.

Director Kobayashi was greatly impressed by Kwaidan and other ghost stories by Hearn and chose to film several of the author’s stories. The result is a uniquely Japanese horror film that is difficult for many Westerners to fully appreciate it. The emphasis is not on gore and violence, but on eerie, almost unbearable atmosphere — a slow and quiet accumulation of details resulting in devastating revelation. The film was shot entirely on indoor stage sets, lit with lurid primary colors. The result is a surreal and strangely artificial world which emphasizes the weirdness of the tales.

The minimalist music is also remarkable. Composer Toru Takamitsu worked with Kobayashi on the explosive film Hara-Kiri and used much the same approach on Kwaidan. Using very few traditional Japanese instruments, often little more than flute and drum, the music adds great foreboding and tension to the film. During the film’s credits, the music is barely there at all, just enough to be heard. This quiet minimalism is a peculiarly Japanese characteristic that fits Kwaidan perfectly.

The first story is “The Black Hair”, adapted from Hearn’s tale The Reconciliation. It tells the chilling story of a status-hungry man who cruelly divorces his faithful wife so he can marry another woman of greater standing. The man’s marriage to his second wife is a disaster and results in his being kicked out of her house. Chastened, the man begs forgiveness from his first wife. The humble woman seems happy to accept him back, but the man later makes a horrifying discovery about her. This is a simple fable with a strong moral element to it but a nasty sting in the tail. Many of the old Japanese ghost stories were to the point but extremely morbid. “The Black Hair” has hints of necrophilia about it — a loveless man is punished for his lack of feeling by a love that extends beyond the grave.

The second tale is “Woman of the Snows” and is generally considered the strongest and most memorable segment of Kwaidan. The central character of the story here is Yuki-Onna, a predatory but beautiful female spirit drawn to snow and ice. Although she is deadly, she is also sad and has a woman’s emotions and tenderness.

An old woodcutter and his young apprentice are caught in a blinding blizzard and take refuge in a remote, abandoned cabin. There, the bone-white but alluring Yuki-Onna appears and freezes the old man to death with her frigid breath. But she takes pity on the young man and lets him live on the condition that he tells no one about her.

Years pass and the apprentice marries a beautiful young girl and has many children by her. But one day the specter of the Yuki-Onna rises once more to terrorize.

The segment is almost too beautiful and unearthly to describe, completely surreal. The strangely lit and obviously artificial settings create the image of a fairy tale world and the snowy scenes in particular are marked by extreme quiet and tension. The first and last appearances of the Snow Woman are startling — not in the traditional horror sense where loud noises and screams predominate, but in seeing something that should not be there. This segment is a triumph of purely Japanese horror.

“Hoichi The Earless” is an even deeper journey into Japanese mythology. It begins with a magnificent recreation of the final sea battle between the Heike and Genji clans, the Japanese equivalent of “The Iliad”. Director Kobayashi is at his best in this sequence. You almost feel as if you are present and witnessing these fantastic scenes. 700 years after the battle, the tale is still told by talented minstrels. One of these is Hoichi, a blind and humble monk residing at a temple. Late one night, when he is the only one left at the temple, a visitor arrives and requests that Hoichi relate the story of the Battle of Dan-no-ura to his master. The blind man finds himself performing the familiar story on his biwa instrument and it slowly dawns on him that he is performing for no mortal audience.

Hoichi’s priestly friends realize what is going on and the head abbot knows that the spirits of the Heike Clan will eventually call the blind minstrel to join them in the land of the dead. Hoichi’s only hope is to have his body covered with mystical insignias to make him immune to the ghost’s influence. There is only one mistake…and remembering the name of this story should clue you in on what it is.

The concluding segment “In A Cup of Tea” is the least satisfying in many ways, but still not without interest. In a strange twist, this tale has its own framing sequence. It is told to us by an author and collector of ghostly stories. The story tells of a samurai who sees the face of a stranger in his cup of tea instead of his own. Dumping the tea in shock, he notices the face appears in his next cup and there is absolutely no one there to cast the reflection. Shrugging, he finally drinks the tea, reflection and all.

That is just the start of his problems, as the next evening he receives a visitor — the man he saw in the teacup. After an argument, the impatient samurai slashes the man with his sword…to no effect. The samurai realizes he has “drunk” a ghost and will now be haunted by the same ghost forevermore.

The idea behind this segment is clever but the framing sequence is clumsy and the denouement unsatisfactory. Given the length of Kwaidan, you could make a pretty good argument that “In A Cup of Tea” could have easily been left out altogether.

Despite this odd ending, Kwaidan remains one of the most unique horror anthologies ever. In fact, it transcends the horror genre altogether and becomes one of the best films about medieval Japan. The pacing is admittedly slow and ponderous, but these stories would not have been served well by a more frantic style. To those really wishing to get a taste of the supernatural mythology of Japan, Kwaidan is absolutely indispensable.

That brings to an end Part One of my look at horror anthology films. Part Two will bring extensive looks at 1972’s seminal Tales From the Crypt and 1995’s African-American take on the form, Tales From the Hood. Until then…pleasant dreams….