Perugia is an ancient Etruscan city that sits in the heart of the Italian region of Umbria. For most, this central city is synonymous with the University of Perugia, which was founded in 1308 and well over a hundred years before Columbus even had a wet dream about finding a new way to India. Like a lot of other universities in Italy’s historic and industrial north, the University of Perugia attracts an international student body, some of whom come from the former Italian colonies of Eritrea, Albania, and Libya. Plenty of Americans have passed through the medieval hallways of the University of Perugia, and like their fellow Étudiants sans frontières, they contribute to the colorful tapestry that is life in an Italian university town.

But like the American university towns and cities which have recently come under increased media scrutiny because of the scourge of sexual assault and rape, Perugia and its campus are not immune to the evils of the outside world. Violence, especially sexual violence, is not unknown in the Comune di Perugia.

Famously, in November 2007, British student Meredith Kercher was found stabbed to death in her apartment, which was located in one of Perugia’s not-so-nice neighborhoods. The investigation into Kercher’s death netted three major suspects—her American flatmate and fellow student Amanda Knox, Knox’s Italian boyfriend Raffaele Sollecito, and the African drug dealer Rudy Guede. It didn’t take the world media long to zero in on the attractive Knox, and soon thereafter “Foxy Knoxy” was the subject of a legal and media circus that tried to portray her as a bloodthirsty monstrosity from the misty city of Seattle.

While most murder trials-cum-celebrity events contain quite a lot in the way of grisly spectacle, Knox’s trial was one for the ages mostly because of the prosecution’s bizarre assertion that Knox, along with Sollecito and Guede, murdered Kercher during a Satanic sex orgy that required a blood sacrifice. A cooler head would claim that the Italian prosecutor Giuliano Mignini had seen one too many horror movies, but the sad truth is that Mignini’s claims in the Knox trial were far from abnormal. The criminal court system in Italy, besides being known for an intricate system of patronage whereby political animals (most of whom seem to either be or were at one point members of the Italian Communist Party) remain in-charge despite previous suspensions or indictments over devious behavior, is also a place where such things as covens and Satanic cults are taken seriously. Before the madness in Perugia, Florence, which also sits deep inside of Etruscan Italy, was the site of another judicial spasm.

Between 1968 and 1985, an unknown killer stalked the Tuscan countryside near Florence. History now knows this man as the “Monster of Florence,” and for the most part, his victims were copulating couples caught in the act. Typically, these youngsters, who had snuck off to some isolated spot in order to make, as Bob Eubanks would say, “whoopee” inside of the cloying confines of Fiat Pandas and Fiat 127s, were killed at night with a .22 Beretta. After death, the female victims routinely had their sexual organs removed.

The investigation into Il Mostro took decades, and despite being an unsolved and cold case, it still acts like a undying leech on Italian society. In particular, the case brought to the forefront personal rivalries, such as the one that existed between Mignini, who subscribed and still probably subscribes to the theory that the “Monster of Florence” killings were the work of a Satanic cabal, and the journalist Mario Spezi, who has written time and time again that Il Mostro was a Sardinian and the son of one of the case’s original suspects. Truth, not Nadine Mauriot and Jean Michel Kraveichvili, was the killer’s final victim.

Amazingly, in 1973, the year before the bodies of Pasquale Gentilcore and Stefania Pettini were found near Borgo San Lorenzo, another killer was busy in the Italian countryside. Wearing a grey ski mask and a red and black ascot, this killer was known to first strangle his victims, then to carve them up postmortem. He was, like the Monster, a butcher, and although he killed men, his preferred targets were women—beautiful, busty women who were more often than naught coeds.

Judging from a distance, this murderer appeared to be the usual sex-obsessed slaughterer who probably had a traumatic childhood that somehow involved duplicitousness on the part of a female, possibly his mother.

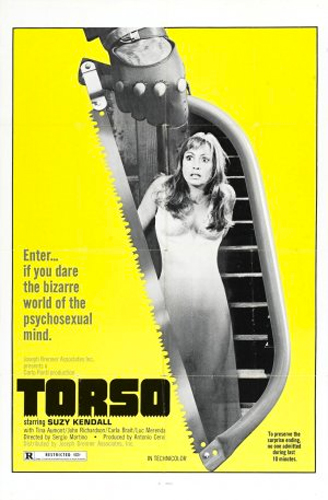

No, this is not a true crime report. Rather, this is the basic outline—the chalky diagram on the deadroom floor—of the central antagonist in Sergio Martino’s Torso. Released in its original Italian as I corpi presentano tracce di violenza carnale, or more simply Carnal Violence, Martino’s slasher classic is a study in the giallo sub-genre. Set partially in Perugia and partially in the idyllic countryside of Abruzzo, Torso depicts extreme acts of violence done in the name of misogyny. White female bodies, both Italian and American, are put through hell, while a lone black lesbian is also subjected to mutilation. Torso is an equal opportunity fright flick, and like the “Blind Dead” films of Spanish director Amando de Ossorio, Martino’s Torso commits its lewd acts without a hint of modesty or even good taste.

Still, despite the film’s sleazy exterior and its softcore porn interludes (which come stock with cheezy ‘70s Muzak and more breasts than the frozen chicken aisle in your local supermarket), Torso is a thriller with more than a few artistic flourishes. Famously, the film contains an almost silent and extended sequence wherein the injured American art student Jane (played by Suzy Kendall) tries to avoid exposing her presence to the killer (played by John Richardson), who busies himself with dismembering the bodies of Jane’s friends from Perugia. Told with an artistic eye that recalls both Terrence Young’s Wait Until Dark and Jules Dassin’s Rififi, this sequence not only helps to establish the auteur credentials of Martino, but also highlights the fact that Torso is more than just a mere slasher film.

In his long career, Sergio Martino directed spaghetti westerns, sex comedies, war films, crime films, and even sci-fi films. His best films though are in the uniquely Italian sub-genre of giallo, and most contain a screenplay co-authored by Martino’s friend Ernesto Gastaldi. Torso’s screenplay is a Martino-Gastaldi collaboration, while All the Colors of the Dark, Martino’s other great work, belongs to Gastaldi and Sauro Scavolini—another one of Martino’s frequent partners. Like the later Torso, All the Colors of the Dark (Tutti i colori del buio) is a sexy thriller that flirts with the horror genre. In that film, an Englishwoman named Jane Harrison (played by the French actress Edwige Fenech) is subjected to the perverted brainwashing of an occult organization that doubles as a blackmailing ring. All the Colors of the Dark is a somewhat trippy film with a hazy plot and an even murkier conclusion. Given its brilliant opening and its excellently executed atmosphere, All the Colors of the Dark should be Martino’s best film, but that honor belongs to Torso.

A clear influence on Eli Roth and his film Hostel, Torso is straightforward where All the Colors of the Dark is meandering. Ostensibly a simple tale of mania and murder, Torso offers a window into the reality of sexual violence. Even though the handsome doctor Roberto (played by the French actor and Martino favorite Luc Merenda) ultimately saves the day, even he isn’t above “the look.”

And what is “the look,” you may ask? “The look” is the sexualized male gaze, and at the risk of sounding like a tired lit. crit. professor, Torso is truly a film about male lust as characterized by the drooling gaze. Women are constantly being ogled by men in Torso, from the horny ascot vender Gianni (played by Ernesto Colli) to the uncouth but virginal student Stefano (played by Roberto Bisacco). Every man in Torso seems like a potential rapist, and therefore each one is a suspect. This is a theme worthy of unnatural paranoia, but Martino reminds us that this is our world and our reality. If nothing else, Torso is a giallo for the real-world; a dark slice-of-life with hapless young women on the menu.

One thought on “Sergio Martino’s TORSO: Bearing Traces of Carnal Violence”

Comments are closed.